December 03, 2021

Stuckeman School professor earns research grant for biodegradable structures

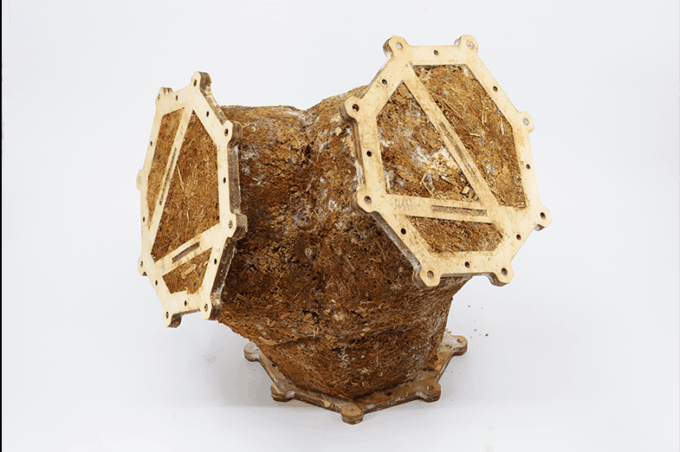

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — A research team led by Benay Gürsoy, assistant professor of architecture and director of the Form and Matter (ForMat) Lab in the Stuckeman Center for Design Computing, was awarded the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Upjohn Research Initiative grant to advance the study of biodegradable building composites made from mycelium, which comes from the root of fungi.

Gürsoy and Ali Ghazvinian, an architecture doctoral candidate whom Gürsoy advises, earned the $25,000 award for their project proposal, “From Waste to Biodegradable Structures with Local Fungi Species.”

The funds from AIA will be matched by the Stuckeman School’s Department of Architecture, giving Gürsoy a total of $50,000 to further research on mycelium-based composites, a biodegradable material that can be used for architectural structures.

“We proposed to build two large-scale prototypes, one called ‘MycoCreateII’ and the other is ‘MycoPrint,’” Gürsoy explained. “We’re exploring how we can 3D print mycelium-based composites for structural use. We want to build a proof-of concept-structure by [3D] printing components of the structure.”

In addition to constructing the prototypes, the grant will go towards other expenses, such as lab tests, materials and supporting architecture students who are working on the project.

According to Gürsoy, the building industry largely contributes to global carbon emissions and landfill waste. Mycelium-based composites provide a solution because they require less energy to form and therefore lower the growing carbon footprint of the industry.

“The energy required to make mycelium-based materials is less than conventional building materials,” said Gürsoy. “However, we cannot say that mycelium-based materials will replace existing building practices right away.”

Another environmental advantage of mycelium-based materials is that they can be cultivated on organic waste materials.

“The fungi need to feed on something to grow during the production process,” explained Gürsoy. “This can be agricultural waste. The composites can be manufactured using this waste and it doesn’t produce any non-compostable waste when it's demolished or crushed and mixed with soil.”

This means, according to Gürsoy, that while using mycelium-based composites in architectural structures is still very experimental, it could decrease the amount of waste that ends up in landfills.

Ghazvinian is investigating the structural capabilities of mycelium-based materials. The project also involves participation from integrated undergraduate-graduate student Natalie Walter, who is growing mycelium-based composites on waste cardboard as acoustic panels, and Alale Mohseni, an architecture master’s student who is focusing on design computing and is assisting Gürsoy with 3D printing mycelium.

The project also has an interdisciplinary nature because of the team’s work with John Pecchia, associate research professor in the Department of Plant Pathology and Environmental Microbiology and director of the Mushroom Research Center Mushroom Spawn Lab at Penn State.

“He [Pecchia] gives us insights about how we can better cultivate mycelium such as what kinds of additives and supplements we can use,” Gürsoy said. “And, most importantly, we are using his center’s facilities for sterilization of the substrates and growing the material in controlled environmental conditions.”

For more news from the Stuckeman School, follow us on Twitter @StuckemanNews.