June 07, 2022

Reimagining Toronto’s waterfront

In the fall 2021 semester, Penn State graduate students explored real-world land use and planning challenges in revisioning Toronto’s waterfront through a 14-week geodesign collaborative studio led by instructor Devin Lavigne. Building on past geodesign curricula, the GEODZ 852 studio continued to provide an immersive, problems-based collaborative studio experience in which students learned about the complexity of urban systems and district-scale landscape change issues alongside various consultants and stakeholders.

Continuing from the place-based complex systems approach of GEODZ 842, the Toronto studio was scaled down from a regional scope to focus on the complexity of urban-developed settings as informed by environmental, cultural and economic frameworks. Prioritizing simulation of the professional experience, students worked in teams and collaborated with professional and local identities, exploring a collaborative approach to design rooted in a local current context.

The studio focused on an 880-acre site east of downtown near Toronto’s waterfront. Due to the area’s history of industry that has since become abandoned, along with the increasing need for flood protection, a disconnected infrastructure and several unrealized development proposals over recent years, the study area was posed as an “opportunity for development.” The area has a unique chance to respond to many needs while attempting to promote future-oriented frameworks for sustainable urban practice.

A crucial feature of the study space was that the site had begun redevelopment already: Google’s Sidewalk Labs had previously forged a controversial and comprehensive plan for the site. The company worked with the Toronto community for more than two years before abandoning the project and withdrawing from the community in May 2020. Thus, a main core of the geodesign student project was to keep the Sidewalk Labs study in mind, assess whether any past plans could be used for present visions and make sure the community could feel comfortable with the introduction of new collaboration and student plans.

The vision of Waterfront Toronto, a local organization, aligned well with a geodesign approach, positing the problem as “an opportunity for governments, private enterprise, technology providers, investors and academic institutions to collaborate on critical challenges and create a new global benchmark for sustainable, inclusive and accessible urban development.” Student decisions were affected by multiple site-considerations, including affordable housing crises, brownfield environmental hazards, flood mitigation and natural reclamation of the neighboring Don River, need for urban amenities and stakeholder development aspirations, and structural connection to adjacent urban areas.

The student projects referenced precedent de-industrialized sites, such as Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Buffalo, New York, aiming to build models of revitalization that preserve cultural heritage, protect natural space and invite present residents to build communities in a shared hub of mixed innovation, recreation, arts and heritage. Using a modular and metric-based approach, the team strategized structural development “one building a block at a time,” proposing foundational urban amenities and assets – such as connection to local marshland and open space, bike trails, innovation campuses and public transit – with intention for the neighborhood fabric to develop over time.

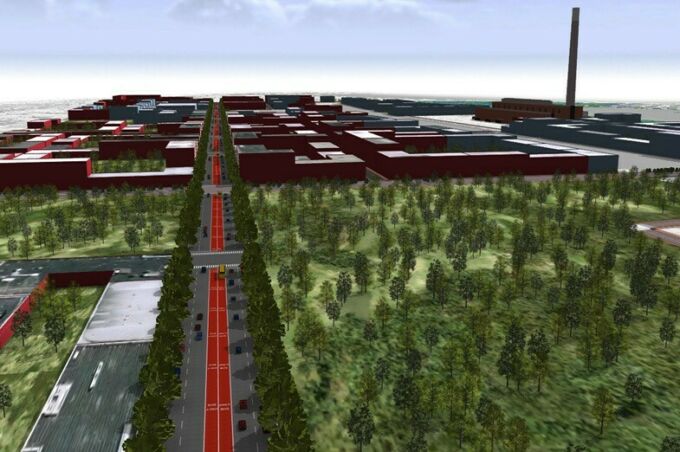

The students used a variety of desktop and online geospatial software tools throughout the semester, which was critical to their work. They used ArcGIS Pro to collect and analyze information on existing conditions, and ArcGIS Urban helped them understand existing zoning districts and which building types and space uses worked best for the site. ArcGIS CityEngine was used to create some realistic renderings of what the site could potentially look like.

Brittany Grant, a second-year student in the online master of professional studies program, enjoyed the variety of tools that were used in the course.

"The tools we used provided a detailed outlook on how future land use would benefit the surrounding area,” said Grant. “Programs like ArcGIS Urban and CityEngine helped construct our vision while also providing detailed information for stakeholders and land developer use. Without these tools, land use suitability would be problematic and difficult to assess."

The final project culminated with an overall plan for the area that tells a story of walkable green networks connecting city centers to existing park space and village-type mixed-use areas. The development proposal includes architecture that honors the history and sense of place and housing and recreational plans that align with naturalization plans with the Don River. The pedestrian-oriented waterfront development area includes pollinator gardens, natural play spaces, educational monuments,and adaptation of existing industrial structures as accessible spaces for arts, recreation, innovation and community use. The plan shows how dynamic, mixed-use development can be woven into an existing urban fabric to build basic foundations for future development in the area.

James Progar, a second-year geodesign student who participated in the course, said “this studio course challenged me technically and conceptually, pushing me further than I could have imagined. The Port Lands was a great site to work with given its historic, industrial and ecological challenges. Being able to work under Devin Lavigne was invaluable to understanding the process and capabilities of geodesign.”

Being a geodesign studio, students used an approach to planning that was characterized by analyzing data, using metrics and responding to simulated measurements to make sure proposed ideas were feasible and could be directly implementable by the community. The interventions suggested were all reasonable so that they made sense to municipal officials who can alter policies and acknowledged constraints, such as land use mandates. The results represented the geodesign framework, in which data informed each step of the design process: context, analysis, ideation, image creation and ultimately presentation, in telling the story to reviewers with ESRI’s StoryMap platform.

The Toronto Studio StoryMaps can be found via arcgis.com. For more information on Penn State’s Geodesign graduate program, visit geodesign.psu.edu.

For more news from the Stuckeman School, follow us on Twitter @StuckemanNews.