May 17, 2022

Dread Scott discusses his process, goals for his artworks in far-ranging interview

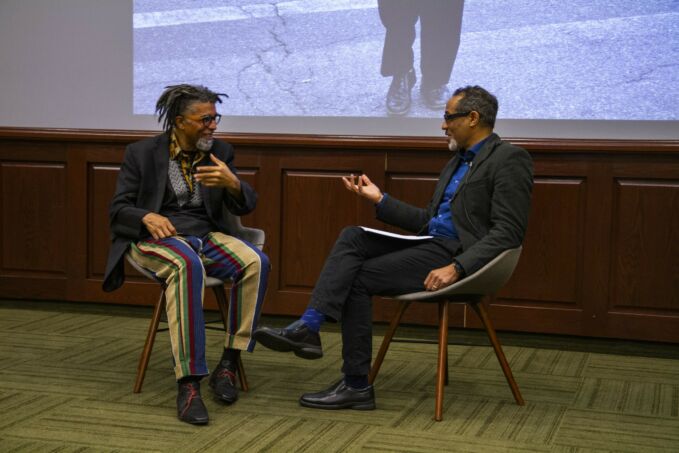

When B. Stephen Carpenter II, the Michael J. and Aimee Rusinko Kakos Dean of the College of Arts and Architecture, interviewed visual artist Dread Scott in Foster Auditorium on May 6, he started off by asking Scott for his “origin story.”

“Where are you from?” asked Carpenter.

“Krypton,” replied Scott.

That set the stage for more than an hour of bantering, story-sharing, and in-depth discussion about some of Scott’s most notable pieces, during which he addressed the why, when, where and how for his often-participatory works in a range of media.

The presentation, co-sponsored by the College of the Liberal Arts, was part of Scott’s visit to campus to deliver the College of Arts and Architecture commencement address on May 7.

Scott’s reply of “Krypton” provided a segue into a discussion of his and Carpenter’s similar Black, middle-class upbringings, Scott in Chicago and Carpenter in suburban Washington, D.C.

Technically a high school dropout, Scott attended private school and thought he would become a scientist.

Screwing up in high school forced me to become an artist and photographer." -Dread Scott

“That accident was kind of a good thing. But it was not predetermined. I probably would have been a decent scientist.”

As a kid, Scott took art classes and dabbled in photography under the guidance of his photographer father.

“My parents gave me instamatic cameras, and an SLR when I got older. They were foolish enough to buy film for this kid – I took pictures of swimming pools. My parents wasted money on a whole roll of swimming pool pictures,” Scott joked.

After graduating from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1989, Scott immediately began exhibiting and creating participatory artworks, prompting conversations about the U.S. Constitution, display of the U.S. flag, slavery and present-day struggles against racism.

For much of the discussion, Scott focused on “Slave Rebellion Reenactment,” the 2019 reenactment of the largest rebellion of enslaved people in U.S. history, which took place near New Orleans in 1811. Hundreds of reenactors marched 26 miles over two days, with even more community members involved in sewing costumes and organizing logistics. Those organizational meetings mirrored the small gatherings of trusted individuals who organized uprisings in the 19th century.

Scott noted that the self-organization of the reenactors was an integral part of the artwork.

“A main thing was the one-one-one conversations [with potential participants], explaining why someone would walk 26 miles over two days in colonial clothing with weapons,” he said. “I got 50 people involved, and then they got other people involved.”

According to Scott, much of his work looks at how the past sets the stage for the present.

“I have a lot of respect for historians, and those people who go into those archives do different work than what I do,” he said. “I’m an artist, which gives me freedom to play with history in a way that historians cannot. Historians cannot make stuff up, but artists can.”

Scott said his research addresses how he can best communicate his ideas.

“The thread that unites all my work is the ideas, the concepts. There is a lot of research with my work. What big social questions do I want to address with my art? How do I use visual language, body language to talk about what I want to talk about?”

During the interview, Scott touched on other pieces, such as “I Am Not a Man” (2009), a one-hour performance in the streets of Harlem that referenced the 1968 Memphis sanitation workers strike where the iconic “I Am a Man” sign originated, and “On the Impossibility of Freedom in a Country Founded on Slavery and Genocide” (2014), where he was sprayed with a fire hose, referencing the 1963 Civil Rights struggle in Birmingham, Alabama, in which the government used high-pressure water jets from fire hoses against non-violent protesters and bystanders.

“In 1968, the Civil Rights movement had already become the Black Power movement,” Scott said. “The striking workers faced the National Guard, who had bayonets. Martin Luther King Jr. had been on his way to support that strike [when he was assassinated]. That is a very important moment in history.”

According to Scott, we are still living in a “racial” America.

“When Obama became president, it was supposed to be the ‘post-racial’ era, but it was still a ‘racial’ America,” he said. “With ‘I Am Not a Man,’ I wanted to show that the Civil Rights movement and, later, the election of Barack Obama did not usher in a post-racial era.”

The presentation concluded with a question-and-answer session, where Scott talked about being a Communist and where he gets his “fearlessness.”

“I don’t think of myself as particularly fearless. I think of myself as someone who sees a problem and possible solutions,” he said. “I think I’m more concerned with what will happen to people I care about if I don’t speak out – I’m just a little concerned about myself.”

See the full interview and question-and-answer session here.