May 26, 2020

Addressing climate change, promoting sustainability through design

Stuckeman School alumna returns to her roots to help design a ‘Living Chapel’ for the Vatican and the United Nations

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — After nearly 18 months of planning, several production hurdles and a worldwide pandemic that shut down international travel, not to mention all of Italy, architect and 2007 Penn State alumna Gillean Denny and a group of students, faculty and research assistants in the Stuckeman School are celebrating the virtual unveiling of a “Living Chapel” they designed to promote environmental consciousness as part of Global Catholic Climate Movement (GCCM) activities in Rome from May 16-24, and the United Nations (U.N.) World Environment Day on June 5. Musician Julian Revie, Denny’s longtime friend and the associate director of music at the Center for Music and Liturgy of Saint Thomas More Chapel at Yale University, was the catalyst for the project. Inspired by the U.N.’s 2030 sustainable development agenda and “Laudato Si” — the 2015 papal encyclical on climate change — Revie worked diligently with Vatican officials to get the plans for the chapel approved and the structure installed. “The chapel is an instrument to inspire a sense of serenity and oneness with nature in those who pass through it,” explained Revie, who was the recipient of the Vatican’s 2016 Francesco Siciliani prize for a sacred music composition. The purpose of the chapel is “to encourage worldwide acts of ecological restoration with an emphasis on tree planting in support of the U.N.’s Trillion Tree Campaign,” said Denny, who earned a bachelor of architecture from the Stuckeman School. The structure, which features green walls that are adorned with living plants and an elaborate chime wall featuring metal embellishments, will officially be introduced via streaming video on June 5 in the Rome Botanical Garden as part of events organized by the Italian Alliance for Sustainable Development (ASviS) in celebration of the U.N.’s World Environment Day. The chapel will eventually be on display at the Vatican, where it will become the second structure in Vatican City to be designed by an American architect. The first was the Chapel of the Holy Spirit by architect Louis Astorino, also a Penn State architecture alumnus. From the Vatican, the Living Chapel will move to its permanent home in Assisi, Italy, as a feature point of a new Saint Francis pilgrimage trail that is being unveiled this spring by the GCCM. The massive structure, which measures 45 feet long by 30 feet wide with walls that range from 10 to 15 feet high, was built out of aluminum and recycled and repurposed materials on the University Park campus during the latter part of the fall 2019 semester and the early weeks of the spring 2020 semester. It was then shipped to Rome, where it was put into storage while travel restrictions were enacted and the country went into lockdown. At that point, Revie and Denny reevaluated their plans from their respective homes in New Haven, Connecticut, and Toronto, Canada. But how did such an elaborate project for the Vatican and the U.N. come about in the first place?The friendship and the idea

Revie and Denny met while they were both attending graduate school at the University of Cambridge. The friends became housemates during their time in the U.K., with Revie introducing Denny to her now-husband, and they would often discuss the possibility of collaborating. After graduating with a master of philosophy and doctorate from Cambridge, Denny became an educator and freelance designer for several years before reducing her professional commitments to start a family. Revie, meanwhile, composed two papal masses and served as a composer and professional organist in Los Angeles before moving on to Yale. Revie had the initial idea of creating a chapel that could be designed to play a musical piece he would compose while furthering the conversation on climate change in time for the fifth anniversary of the pope’s Laudato Si. A member of the Catholic church, Revie also wanted to pay homage to St. Francis of Assisi, who is known in the faith for his love of nature.There was a moment that I knew I wanted to be a part of this project, but I also knew that I could not design and build what we had in mind by myself.” – Gillean Denny, 2007 architecture alumnaAfter much discussion with members of the Vatican and theologians worldwide, Revie was frustrated by the lack of a single design vision for the chapel, which is when the idea of collaborating with Denny reemerged. As a fellow Catholic with a professional background in sustainable design, urban agriculture and theatre production, Denny seemed ideal to help solidify the chapel vision. They decided to begin precisely as St. Francis did. “It is said that when Francis received a message from God to ‘go build a church,’ he took the directive literally and built a prayer chapel,” explained Revie. “We wanted to reimagine that structure.” The church built by St. Francis — Porziuncola — still stands in Assisi and resides within the larger Basilica of Saint Mary of the Angels, which was built to accommodate the visitors that come to pay homage to the saint. The site has since been named a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The vision for the Living Chapel took on a life of its own, and the scope was immense. The pair knew they needed help to pull it off. “I was really intrigued by the idea [of the chapel], but I thought Julian was completely insane for wanting to have something of this scale finished by early 2020,” said Denny. “Then as we discussed it more and started fleshing out ideas, the less crazy it seemed and the more excited I got. There was a moment that I knew I wanted to be a part of this project, but I also knew that I could not design and build what we had in mind by myself.” By then it was the spring of 2019 and Denny decided to seek assistance from the place that fueled her passion for design-build projects and Italian architecture.

A tradition of design-build

The Department of Architecture in the Stuckeman School at Penn State has a rich tradition of design-build curricula, beginning in the first year of the five-year professional bachelor of architecture program. Students learn the importance of not only designing a structure, but the physical process of putting together their design projects by hand, using real building materials. Traditionally, students in the fourth year of the program are required to study for a semester in Rome at the Pantheon Institute, where they experience firsthand the historic and contemporary architecture, landscape architecture and urbanism of the city. James Kalsbeek, an associate professor in the department since 1990, specializes in leading design-build projects with students in both the first-year studio and a more advanced seminar where students work exclusively with discarded and reclaimed building materials. He also has been involved with the Rome program since its inception in 1991 and led the program in fall 2005 when Denny studied in Rome. Kalsbeek’s familiarity with design-build projects and Rome itself put him at the top of Denny’s list of people she wanted involved in the chapel project. “I was thrilled when Gill called and explained what she was up to,” said Kalsbeek. “It was a huge undertaking, sure, but it was something I knew she was quite capable of doing because she had done it here as a student. Maybe not to the same scale, but it became sort of a running joke that she was an expert at designing and building structures that were made to end up somewhere else.” Denny did her fair share of designing installations around campus during her time as an undergraduate, and more specifically, she had experience building green structures. Denny was the lead designer for the Penn State team that conceptualized the MorningStar solar home during her fourth year of studies. That structure was built on campus and shipped to Washington, D.C., for the 2007 Department of Energy Solar Decathlon. It was then on display in several locations before returning to its home on the University Park campus....it became sort of a running joke that she (Denny) was an expert at designing and building structures that were made to end up somewhere else.” — James Kalsbeek, associate professor of architecture“Getting that hands-on experience — actually getting in there and touching the materials you are working with and seeing how they respond to each other and the elements — was something I got away from in my career with a family, so it was really exciting to get back out from behind a desk,” said Denny.

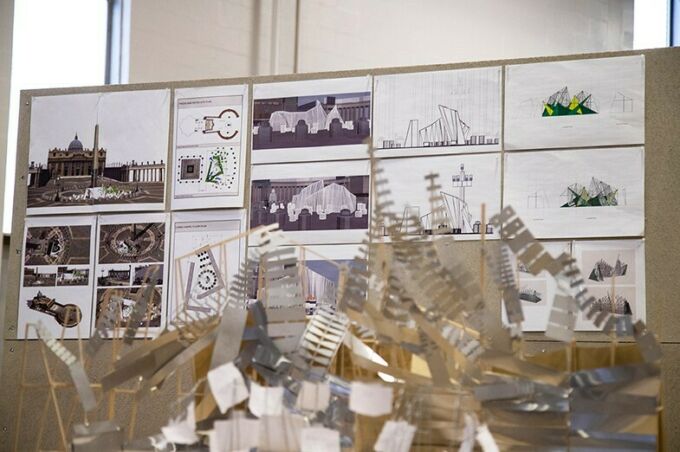

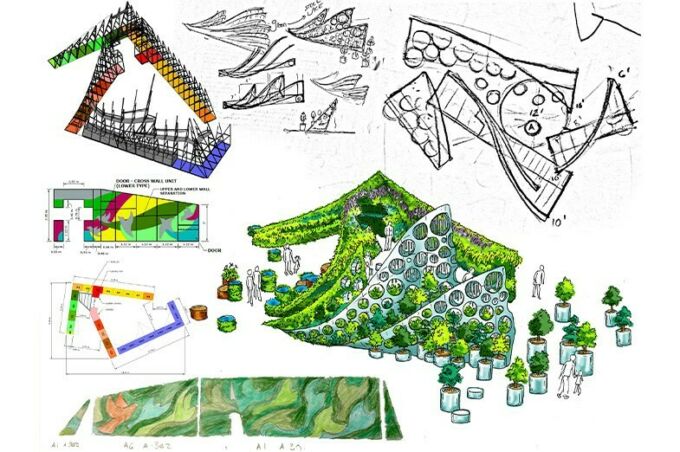

The structural frame

Denny and Revie presented their design ideas to Kalsbeek during the summer of 2019 with the understanding that this was a large-scale green project. It would need to be fabricated and assembled in a modular fashion at Penn State, then taken apart and shipped to Italy where it would be reassembled and covered with tree and plant saplings by Italian botanists at the Rome Botanical Garden. Kalsbeek located a workspace large enough for their needs — the Laundry Building on campus — and assembled a “dream team” of students and researchers with expertise in building foundations, methods of assembly, fabrication processes, green structures and materials research that could work together to build the traveling, green, artistic, musical structure Revie and Denny envisioned. That core team included architecture doctoral student Elizabeth Andrzejewski, graduate students Elizabeth Rothrock and Kacie Ward, and research assistants Becca Newburg, Garrett Socling and Dani Spewak, an alumna of the School of Visual Arts. “I honestly didn’t think the project would come together given how short the timeframe was for all of the work that needed to get done, but I wanted to help,” said Andrzejewski, a skilled welder whose master’s thesis at Penn State was on jointing systems for prefabricated architecture and her doctoral research focuses on the interaction of materials and processes. “It seemed impossible, but given the significance, of course I wanted to do what I could to see it through.” First up was tackling the chapel’s structural frame, which is where the team encountered one of its first production challenges. “It was obvious right from the start that while Lizz (Andrzejewski) is an amazing welder, we only have one of her and we just knew that we didn’t have the resources here that we needed to fabricate a structure of this size,” said Ward. “We had to look elsewhere to get help.” That “elsewhere” ended up being 60 miles away at the Pennsylvania College of Technology in Williamsport, which is known for its welding and metal fabrication programs.“Luckily, we designed and assembled the chapel in a modular fashion to begin with, so it is sort of meant to be taken apart and put back together without disrupting the systems.” — Elizabeth Andrzejewski, architecture doctoral studentKalsbeek and Denny met with Penn College officials, including James N. Colton II, co-department head of welding and metal fabrication. “Gillean came to our campus to meet with the team of faculty and students we assembled in September [2019] and we were asked if we could build the four walls for the chapel here,” said Colton. “We were talking about the materials we could use and decided that in order to keep the structure from getting too heavy, using aluminum was our best bet.” In total, 4,956 feet of aluminum was used to construct the walls, which is about 16 football fields in length, and 3,514 combined hours were spent by the Penn College team on the project. The work by the Penn College team was absolutely essential in getting the structural framework of the chapel built, said Denny. “They literally were working miracles on that campus through Christmas break and into the new year,” she said. “But no way, no how, did the chapel get built without them. Period. They were amazing. Jim [Colton] and I were in constant contact every day, double-checking details as they worked and making changes as necessary.” With the internal skeleton of the chapel completed and shipped to University Park in late January 2020, the Stuckeman School team got to work cladding the walls of the massive structure.

Building a musical, green chapel

Revie and Denny wanted to incorporate recycled and reusable materials into the chapel, so they started reaching out to friends and sharing details of their project in order to drum-up interest. “One of my old Penn State friends has a connection we thought could help and long story short, that’s how we ended up getting more than 1,500 pounds of donated parts from two automotive metal stamping plants,” said Denny. Revie also arranged for the donation of discarded oil drums and steel pan drums from a manufacturing plant. Each drum had a production flaw and would have been thrown out as scrap, yet they played beautifully. With her strong welding background, Andrzejewski focused on the fabrication and mounting of steel pan drums from the donated parts on the chime wall, which was to be the chapel’s focal point. Newburg, a 2018 architecture alumna who has a background in fabrication, took interest in designing the series of drums that were to be part of Revie’s musical composition in the tradition of the instruments from the islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The drums are located inside the structural framework of the four walls. Newburg also worked with Denny to design the intricate metal screens of plants and suspended cross cutouts made from donated parts on the wall. Wind that flows through the chapel’s rolling layout will move the crosses to have a windchime effect while also reflecting light. “When we had a good design [for the drums], we had to figure out how to make 37 of them that were rugged and durable so they would last,” she said. “At that point, we recruited 24 talented undergraduate architecture students to help and essentially set up a factory floor, explaining what they had to do at each station, so we could mass produce the pieces we needed.” According to Kalsbeek, an additional eight students clocked dozens of hours on the CNC router in the Stuckeman Family Building, mass producing the custom-patterned metal panels with guidance from Jamie Heilman, the Stuckeman School’s digital fabrication and specialized technologies coordinator. Meanwhile, Socling got to work designing the solar-powered irrigation system that circulates water through the green walls of the chapel. He also helped determine how the steel drums in the chapel framework would play. “We have a frame around each drum that has brackets which hold a mallet that is positioned above the note on the drum it is to play,” explained Socling. “At the other end of the mallet, we fastened a 3D-printed cup that we made, which fills up with water from the irrigation system and brings the mallet down to strike the drum on the intended note while it empties with water into a cup with a mallet positioned on a specific note on the drum underneath it and so on.” Rothrock, who graduated on May 9 with a master’s degree, is adept at understanding building materials and how they work with each other. “Since our core team has a variety of research focuses, we were all able to benefit the design of the project in different ways,” said Rothrock. “We were all able to contribute our unique knowledge to the structure, which is why, I think, it is successful.”Regrouping to bring the chapel ‘to life’

While the team from Penn State was set to travel to Rome to help Denny assemble the structure during spring break, with help from the fourth-year architecture students who were studying abroad at the Pantheon Institute, those plans were scrapped when the coronavirus pandemic erupted. The group needed to regroup and change course due to a hurdle no one could have predicted — a worldwide health crisis. “We decided that to ensure everyone’s safety and to still meet the scheduled opening in mid-May, it was best to ask an Italian architecture firm to handle the assembly of the chapel,” said Denny. Sequas, a Rome-based firm that was originally brought on to the project to verify the structural drawings for the chapel’s eventual installation in Assisi, handled the reassembly in the Rome Botanical Garden. “Luckily, we designed and assembled the chapel in a modular fashion to begin with, so it is sort of meant to be taken apart and put back together without disrupting the systems,” said Andrzejewski. The original plans for the chapel called for up to 10,000 saplings, cultivated from the Botanical Garden’s own trees and other participating nurseries, to be featured on or around the chapel. The idea was that the saplings would then grow enough to cover the structure by the time the chapel was unveiled. Since those saplings continued growing while plans for the chapel were on hold as the COVID-19 pandemic surged, they are now too mature to install on the walls and are planted in pots throughout the chapel. Those trees will be distributed upon the chapel’s public opening to be planted in other parts of Italy where deforestation has taken place. The green walls of the chapel are adorned with 3,000 perennial plants — a mix of evergreen leaves and flowers — that form a mosaic pattern. They are affixed to the walls with recycled fleece fabric that is stapled to PVC board. Other areas of the chapel also include trees and plants to reflect the rich biodiversity of Europe’s old growth forests, which have been almost entirely lost due to deforestation. “The plants, which were grown by Verde Vertcale, were chosen based on how they would look in late May or early June when we originally were planning to have the chapel open at the Vatican,” explained Denny. “It was really important for us to present the opportunity of hope and being able to turn around some of the destruction that man has caused on ecosystems. We worked very specifically on the patterns of the plants, which becomes a visual concentration of the piece in and of itself.”Coming full circle

While the project didn’t conclude with a grand opening at the Vatican next week with both the Penn State and Penn College teams in attendance as originally planned, Revie and Denny said they are thankful they were able to pull together virtually to debut the chapel. “We did what we set out to do, and we can all be very proud of that fact. The Living Chapel exists as the message it was meant to be — one of reflection, serenity, hope and action to help our planet and the environment now,” said Denny. “People can see it digitally, for now, and hopefully — in the future — our teams and the wider world will be able to visit it in person, to fully appreciate the impossibility we made possible.” The Stuckeman School team is also thankful to have been involved in such a meaningful, and historic, project that brings together art, architecture, music and nature in a sacred space. “The Living Chapel project has brought together everything I love: students building real things, the creative use of discarded stuff, Rome, music and the ceremony of construction — and saving the planet isn’t bad either,” said Kalsbeek. “But what I love even more? That I was in a unique position to recruit a very select group of students from all levels of the department — from first-year students to Ph.D. students — to form a dream team that I knew could help Julian and Gill realize this important project. I knew it was a once in a lifetime opportunity for all of us, and I knew our students were up to the challenge.” After the chapel moves to the Vatican, it will eventually make its way to its permanent home in Assissi, near the chapel built by St. Francis, patron saint for ecologists. Updates on the Living Chapel and its June 5 opening can be found via Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.